3.6 Cusping

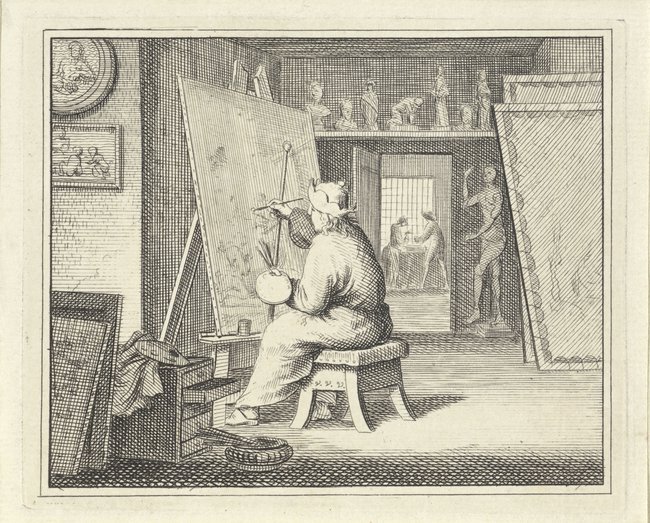

The next stage in the process of preparing the canvas to be painted was the application of a layer of glue and a ground. This could take place in the workshop of the painter or elsewhere by a specialized craftsman, called plamuurder or primuurder in Dutch and primer in English. Glue was applied to make the fabric less penetrable to the ground, while the ground, which could consist of one or more layers, provided a smooth surface and a uniform color. In order to apply the glue and ground, the canvas was stretched on a wooden framework which was usually larger than the canvas, and was fastened with either strings or nails. This stretching caused curved deformations in the fabric along the edges of the canvas between the points where the canvas was attached to the wooden framework. This is called primary cusping, and can be seen in the large stretched canvases in the background of Figure [1]. This cusping was fixed in the fabric when the applied glue and ground hardened.

Because the original tacking edges, with which a painting is attached to a wooden stretcher, have often been removed during past treatments, the study of cusping can be useful in questions of format. The absence of cusping along the edges of a canvas may indicate that a painting has been cut down from its original size. This is the case with Vermeer’s Diana and Her Nymphs (L01) of circa 1653-1654. The suspicion that the right-hand side of this painting has been cut off in the past was confirmed by the absence of cusping on this side. During the restoration of 1999-2000, when the lining canvas on the backside of the painting was removed, clues were found that 12 cm of the original canvas are missing from the right-hand side.1

In comparison with the work of other contemporary painters, a relatively large number of Vermeer’s paintings has preserved their original tacking edges.2 When the original tacking edges are still there, it means that a painting has retained its original dimensions. Vermeer’s The Little Street (L11) is an example of such a painting with four original tacking edges. Although this painting has not been cut off, only the top and the left side of the canvas show primary cusping. This lack of primary cusping along two edges of this canvas is in all probability because the canvas was cut from a larger piece of primed canvas. Evidence that large pieces of primed canvas were for sale, can be found in a seventeenth-century document. The aforementioned inventory of paint dealer Van Bubbeson records several strips of primed canvas in various sizes, such as nine ell long, two ell wide (circa 630 x 140 cm) and 10 ell long, 7/4 ell wide (circa 700 x 122,5 cm).3

1

Vincent Laurensz. van der Vinne (II), A Painter in his Studio, etching. The cusping along the edges of the canvas is clearly visible in the large paintings in the background.

Notes

1 P. Noble et al., Preserving our Heritage: Conservation, Restoration and Technical Research in the Mauritshuis, Zwolle 2009, p. 166.

2 Costaras mentions sixteen paintings with original tacking edges on all four sides: Costaras 1998 (note 4), p. 167.

3 X. Henny, ‘Hoe kwamen de Rotterdamse schilders aan hun verf?’, in: N. Schadee (ed.), Rotterdamse meesters uit de Gouden Eeuw, exh.cat. Rotterdam (Historisch Museum) 1994, pp. 43-53, esp. pp. 49 and 53 (note 85).